Ever since medical school, Christopher S. Ahmad, M.D., chief of sports medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia and team physician for the New York Yankees, has been fascinated by the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL), which connects the upper arm and forearm and helps support the inner elbow during throwing motions. “The fact that this small ligament endures so much stress and is able to survive and allow baseball players to have the careers that they do is amazing,” says Dr. Ahmad. “And as a surgeon, we have this amazing capacity to put the ligament back together and preserve the careers of baseball players, thanks to the development of the Tommy John surgery.”

Named after the Major League Baseball pitcher who was the first to receive the procedure, the Tommy John surgery was created in 1974 by then Los Angeles Dodgers’ team physician Dr. Frank Jobe, who transplanted a tendon graft from John’s non-pitching arm to reconstruct his damaged UCL. Not only did the revolutionary surgery save John’s career, but it also changed sports medicine.

Over the past 30 years, Dr. Ahmad, who completed a fellowship with Dr. Jobe, has worked to improve the surgery and make it more reproducible. Below, he explains how the evolution of the sport has demanded evolution of the procedure as well, and how the latest surgical development stands to improve outcomes for athletes.

What Dr. Jobe initially pioneered was incredibly successful, but modern baseball players have changed. They’re bigger and stronger, they throw harder, and they throw designer pitches. They also throw with more ball movement, which requires a stronger grip on the ball. All this is putting a level of stress on their elbows that we’ve never seen before.

— Dr. Christopher Ahmad

Understanding The Growing Stress on Players and Their UCLs

I’ve dedicated my career to refining and advancing the techniques we use to reconstruct and repair the UCL. What Dr. Jobe initially pioneered was incredibly successful, but modern baseball players have changed. They’re bigger and stronger, they throw harder, and they throw designer pitches. They also throw with more ball movement, which requires a stronger grip on the ball. All this is putting a level of stress on their elbows that we’ve never seen before. Players are injuring their UCLs more frequently at every level; in fact, approximately 35% of active MLB pitchers have had Tommy John surgery.

X-ray demonstrating an ossification within the UCL from chronic use.

This epidemic is happening because of how much velocity is celebrated in baseball. The more velocity you have, the more effective you are as a player, but that higher velocity puts more force on the UCL. And this no longer impacts only pitchers; now position players are injuring their UCL.

Dr. Jobe, along with Dr. Neal ElAttrache and Dr. Lewis Yocum, who were also pioneers of the surgery, taught me how to do this operation. They also taught me to think critically about how we perform Tommy John surgery and why we need to continue innovating the procedure.

Even before my fellowship with Dr. Jobe, I knew of the surgery and had already done some research on it. As a fellow, I did more advanced research into reconstruction techniques and noticed subtleties to the surgical technique and ways to improve it. It’s what inspired me to spend my career enhancing the treatment of baseball players with UCL injuries. And as the pressure on players increases, we need advanced research and innovation now more than ever to improve recovery and rehabilitation, and allow athletes to return to sport.

Most recently, my colleagues and I conducted a retrospective analysis evaluating the return to performance of MLB pitchers one, two, and three seasons after getting Tommy John surgery. We identified 119 MLB pitchers who underwent primary UCL reconstruction or repair from November 2017 to November 2023. Of those, we analyzed return to performance on 54 pitchers who met our inclusion criteria of having at least two qualifying seasons of post-operative data.

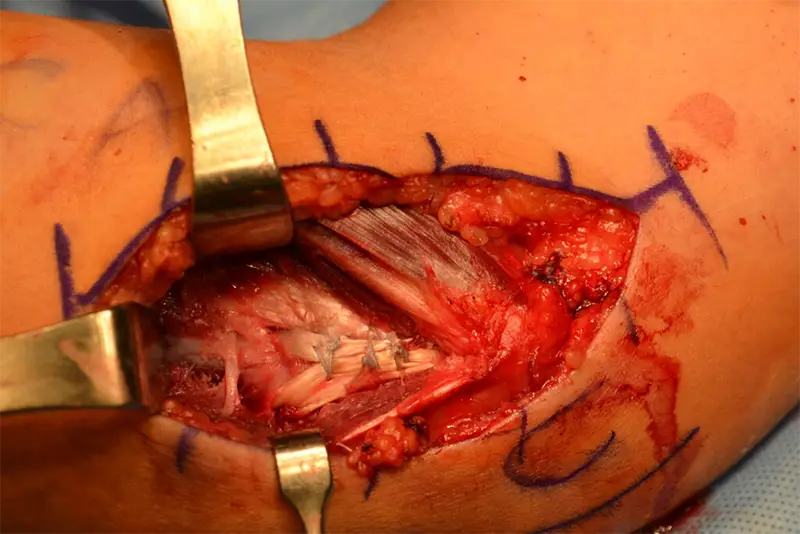

Tommy John reconstruction surgery

What we found confirmed what we already knew: It takes a long time for players to rehab and recover from UCL surgery and regain performance levels. The statistics are staggering: Only 4%, 12%, and 28% of pitchers returned to full pre-operative performance one, two, and three seasons afterward, respectively. Our findings provided even more evidence that players need better recovery from Tommy John surgery to sustain effectiveness — both in time and durability.

The Next Evolution in Surgery: The Triple Tommy John Procedure

Looking back on the past 50 years, so much has changed about the surgical approach to the Tommy John procedure.

We can now use synthetic materials to protect the reconstruction and repair of the native ligament. I’ve worked with orthopedic surgeons across the country like Dr. Jeff Dugas and Dr. Keith Meister to develop new techniques that repair and reinforce the UCL, including the docking technique and the UCL internal brace. Repairing the UCL has benefits over reconstructing the ligament — it involves faster healing because we use native tissue rather than transplanted tissue.

However, not everyone is a candidate for repair. If the tear pattern is profoundly damaged, the patient would benefit from a reconstruction, which involves transplanted tissue. We know that this method takes longer to heal, so my colleagues and I have been working on ways to perform a combined repair and reconstruction technique that offers faster recovery with fewer setbacks and better career longevity.

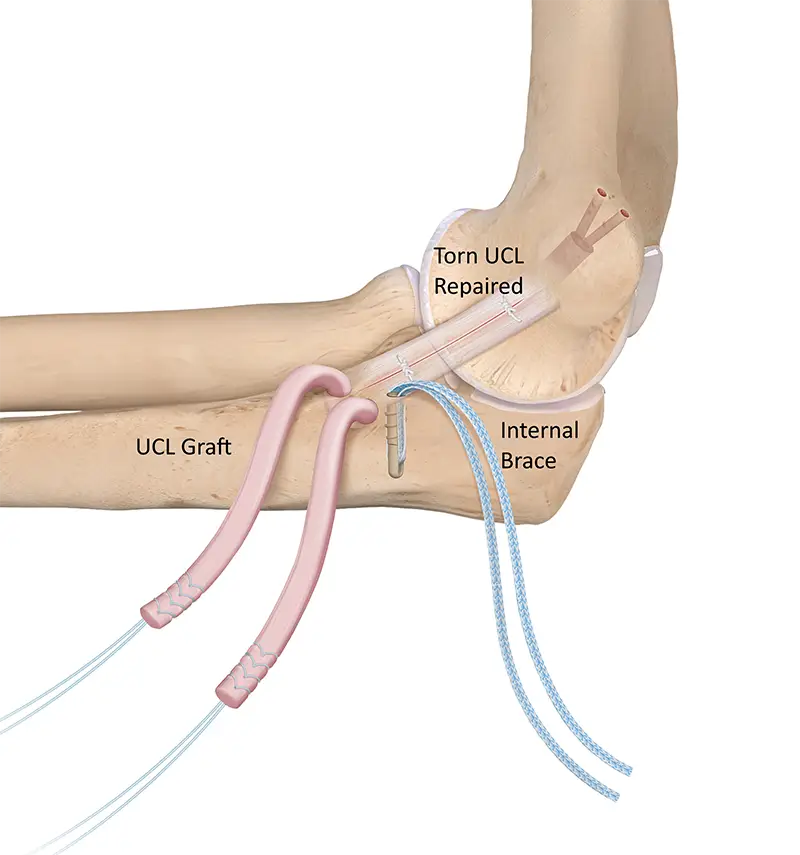

Triple Tommy John surgery combines repair of the native ligament, use of an internal brace, and reconstruction of the ligament to offer greater strength and durability and maximizes the chance of a successful recovery.

The Triple Tommy John (TJ3) procedure is the result of that investigation. This is a significant advancement in UCL reconstruction, and it involves three components:

- Repairing the native ligament utilizing strong sutures to encourage natural healing and restore the ligament’s original function. This technique uses a small anchor inserted into the bone to secure the repaired ligament, improving stability and promoting healing.

- Use of an internal brace to provide extra support and protection for the UCL. The brace is secured to both the ulna and humerus at the medial epicondyle and acts as a reinforcement for both the repaired ligament and the reconstructed ligament, helping to prevent it from tearing again.

- Reconstructing the ligament using a graft, typically taken from a tendon in the wrist or below the knee. Holes are drilled into the bone near the native ligament’s attachment points and the graft is woven through these holes, secured in a docking fashion. While the reconstruction takes the longest to heal, the internal brace protects it during the healing process.

The combination of these three components results in a more comprehensive and robust reconstruction that offers greater strength and durability and maximizes the chance of a successful recovery. Historically, recovery from Tommy John surgery has taken anywhere from 12 to 18 months; however, there is the potential for accelerated healing with TJ3 due to these innovative techniques. I have already been performing this surgery for a few years on players of all levels, and the results I’ve seen have been tremendous. TJ3 has the potential to truly transform UCL surgery and recovery.

While innovating Tommy John surgery is incredibly important to making recovery as successful as possible, we also need to focus on prevention of these injuries. That includes two important components – identifying how to predict when someone could potentially injure their ligament and curbing the epidemic of elbow injuries in young athletes.

— Dr. Christopher Ahmad

Going Beyond Surgery

While innovating Tommy John surgery is incredibly important to making recovery as successful as possible, we also need to focus on prevention of these injuries. That includes two important components – identifying how to predict when someone could potentially injure their ligament and curbing the epidemic of elbow injuries in young athletes.

We need to continue examining pitcher mechanics and fatigue. If we can measure fatigue, that can help us predict if someone’s at risk. We also are looking at modalities that allow us to image the elbow better to see if the ligament and other tissues are more susceptible to injury.

The quest for velocity is also pushed in early professionalization and specialization of younger players, leading to UCL injuries becoming more common in college and high school athletes — and sometimes even younger. We need to ensure that our young athletes are doing adequate strength training and using optimized throwing mechanics. I serve on a research committee for Major League Baseball that is supporting a multicenter registry, which will document all the elbow injuries in youth, college, and professional athletes on a global scale. I also cofounded the Baseball Health Network, an organization that provides educational resources to help parents and coaches keep young players healthy and understand how to prevent elbow injuries from happening in the first place.

I feel extremely honored to do what I do, and I am so fortunate to have people who have inspired and supported me along the way. I am dedicated to training up-and-coming orthopedic surgeons in the latest Tommy John surgical techniques so that we have physicians who will not only keep this legacy going but will continue to improve on what Dr. Jobe started in 1974.