Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the leading cause of death in athletes under 35. Denis Donovan, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/

Unlike with athletes over 35, in which SCD is often caused by coronary artery disease, SCD in younger athletes is primarily tied to underlying cardiac problems that can easily go undetected. “The challenge with this lies in the fact that many of these conditions are clinically silent, meaning that the sudden cardiac event is often the first presentation of the illness or the first time that patients or their families learn that they have something wrong with their heart,” says Dr. Donovan.

SCD and other serious cardiac events in young athletes are uncommon but jarring when they do occur, often making headlines, as with the recent case of rising college basketball star Bronny James, who went into cardiac arrest this past July. “The incidence of SCD is not completely known, but in the United States, large reviews of these episodes over a 20 or 30-year period have found that there's a few dozen a year,” Dr. Donovan explains. “These incidences, though rare, are devastating to individuals, to families, to the communities in which they occur. So, there’s a lot of research and efforts around screening to try to identify subtle red flags and identify athletes who are at risk before the event occurs.”

These incidences, though rare, are devastating to individuals, to families, to the communities in which they occur. So, there’s a lot of research and efforts around screening to try to identify subtle red flags and identify athletes who are at risk before the event occurs.

— Dr. Denis Donovan

Dr. Monaco adds that, in reviewing some cases where an athlete was resuscitated after a cardiac event, “you can often find subtle clues that might have brought to light answers to some of the screening questions that would’ve prompted further testing.”

Current Guidelines

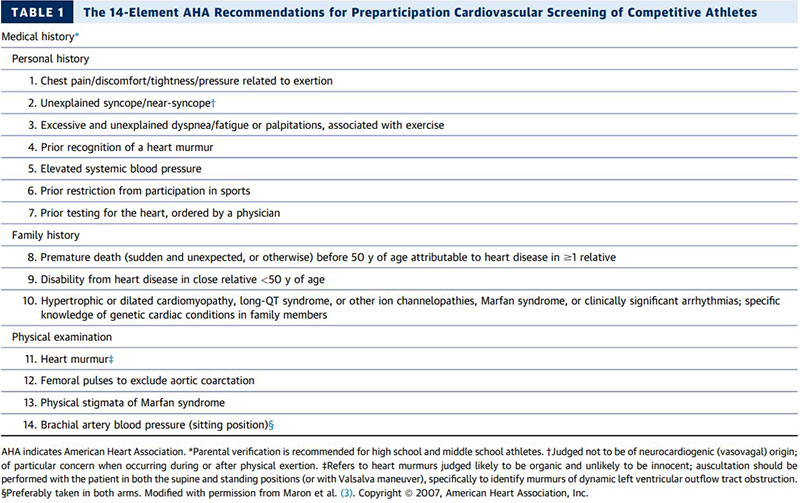

In a review recently published in Current Opinion in Pediatrics, Dr. Donovan and Dr. Monaco, along with Joanna Nelson, MD, a pediatric cardiology fellow at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia, examined the preparticipation screening recommendations of different medical societies in the U.S. and abroad. The current recommendation of the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC), they explain, is a 14-question screening that encompasses three different categories: history, family history, and a physical exam. “If anything is found to be positive or abnormal on that screen, then the recommendation is that the patient is referred for subspecialist evaluation with a pediatric cardiologist to consider additional testing, which usually would consist of an electrocardiogram (EKG) and often an echocardiogram,” says Dr. Donovan.

Preparticipation screening is typically done in early adolescence when school sports reach a new level of intensity. While there is no exact timeframe that screening must be performed, the general recommendation is for athletes to undergo screening about six weeks before the start of their sport. This way, Dr. Donovan explains, if any abnormality is identified, there is still time for specialist referral and additional testing.

The 14-Element AHA Recommendations for Preparticipation Cardiovascular Screening of Competitive Athletes.

Sourced: Maron BJ, Friedman RA, Kligfield P, et al. Assessment of the 12-lead electrocardiogram as a screening test for detection of cardiovascular disease in healthy general populations of young people (12-25 years of age). J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:1479–1514.

The Screening Debate

Though screening athletes for sports participation is a widespread practice, the authors add that certain processes and screening tools, specifically EKGs, have been long debated among experts. While the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), International Olympic Committee (IOC), and the Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) recommend universal EKG screening in the preparticipation evaluation of young athletes, the AHA and ACC in the United States currently do not.

“The sensitivity and specificity of EKG screenings are imperfect and can occasionally yield false positive results, meaning minor abnormalities that are not necessarily associated with a condition known to be a risk for sudden cardiac death,” says Dr. Donovan. “The recommendation in the United States is that EKG screening should not be universal at this time, but rather should be performed if the initial screen identifies an abnormality.”

The authors also added that, with about seven and a half million young athletes in the United States, including EKGs in universal preparticipation screening not only presents a gray area for test results but may also be cost-prohibitive and a significant obstacle for logistics.

Participation Restrictions & COVID-19

In addition to preparticipation screening, the AHA and ACC provide guidelines for disqualifying or restricting young athletes from sports when their health presents a safety issue The authors report that these recommendations can be used as a framework for clinicians, and the decision to return to play should be a shared decision-making choice involving the clinician, patient, and their family or caregivers.

COVID-19 may also be a consideration when evaluating a young athlete’s heart health, the authors say.

“A lot is still unknown but there have been recommendations put into place, which, in short, say that those who have a history of asymptomatic, mild, or moderate previous COVID-19 infection do not appear to be at or not known to be at an increased risk,” says Dr. Donovan. “However, those who have had more severe COVID-19 with evidence of myocarditis should be managed similarly to patients with myocarditis from other causes which does mean restriction from participation pending further evaluation and a period of recovery.”

Looking Ahead

As for whether some sports pose a bigger risk to cardiac health than others, Dr. Donovan and Dr. Monaco emphasize that, though football and basketball are “the most commonly implicated” sports in the United States (along with soccer, globally), SCD can happen during any physical activity. “It’s less the sport itself, and more an issue of people with an inherent underlying risk participating in high-intensity dynamic physical activity,” says Dr. Donovan.

When it comes to the future of cardiac screening in sports, the authors are optimistic about making the current recommendations more accessible to other providers throughout the country, but they know they have a ways to go.

“The participation rate of doing the full 14-point screening is not perfect,” Dr. Monaco explains. “There's a lot that can be done from an education standpoint of first-line providers.”

“Even one death of a young athlete is too many,” says Dr. Donovan. “And while screening certainly has been credited with decreasing these events, the goal is to limit this risk even further.”