The influence of serotonin in cardiac valves has been known for decades. Researchers at NewYork-Presbyterian/

“A type of neuroendocrine tumor, most commonly known as a carcinoid tumor, produces high levels of serotonin. Patients with tumors that secrete serotonin often develop cardiac valve disease; their cardiac valves get thicker,” says Estibaliz Castillero, PhD, Associate Research Scientist in Cardiothoracic Surgery Research in the Department of Surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/

Dr. Castillero noted that with this clear association between increasing serotonin and valve disease, it was easy to make the leap to study SSRIs, which also increase serotonin in the brain. “Clearly, the effect of SSRIs in the cardiac valves has not been as dramatic as the diet drugs considering that millions of people take an SSRI, sometimes for decades, so we wanted to study whether a more subtle effect may be going on in mitral valve disease.”

Dr. Estibaliz Castillero

Dr. Giovanni Ferrari

To this end, Dr. Castillero and Giovanni Ferrari, PhD, Scientific Director of the Cardiothoracic Research Program at Columbia, undertook a multicenter study in collaboration with Dr. Robert J. Levy at the Pediatric Heart Valve Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Valley Hospital Heart Institute, to determine if serotonin could potentially accelerate degenerative mitral valve regurgitation.

“While there have been previous studies on serotonin and cardiac valves, they did not focus on degenerative mitral regurgitation in particular,” says Dr. Ferrari. “In addition to the studies on neuroendocrine tumors and Fen-Phen effects, a few studies in animals supported a role for serotonin in mitral valve disease. It was already known that SERT knockout mice have thickened mitral valves. There are certain breeds of dogs that tend to develop degenerative mitral regurgitation, and they also happen to have increased blood serotonin. In 2019, regarding SSRI, we performed a meta-analysis on serotoninergic drugs and valve disease and we found an association between SSRI and valvulopathy, but we did not study the mitral valve specifically.”

In their current study, Drs. Castillero, Dr. Ferrari, and their collaborators hypothesized that a decrease in the activity of the serotonin transporter (SERT) in the mitral valve advances the remodeling that leads to degenerative mitral regurgitation and tested this on two clinically relevant scenarios. Was decreased SERT activity caused by SSRI use or by specific SERT promoter genotypes?

The study enrolled 263 patients undergoing first-time valve repair or replacement surgery for degenerative mitral regurgitation (DMR) surgery. Tissue specimens were collected from 87 patients undergoing DMR surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/

We interpret the role of SERT in primary mitral regurgitation not as a risk factor for causing mitral valve disease but as a risk factor for enhancing progression of the disease.

— Dr. Estibaliz Castillero, Dr. Giovanni Ferrari, and study co-authors

Is a Specific Genotype Involved?

The researchers also investigated a particular genotype (5-HTTLPR) in SERT, which is involved in the deactivation of serotonin, finding that gene expression of serotonin-associated proteins is altered in degenerative mitral regurgitation leaflets versus normal mitral valve leaflets. “It does seem that if a patient has the ‘long-long’ version of the 5-HTTLPR region of the gene, the effect of SSRI on the progression of DMR may be stronger,” explains Dr. Castillero. “The main biological effects of serotonin happen when serotonin binds receptors on the surface of cells, sending a signal to the cell to act accordingly. The transporter SERT takes serotonin from outside to inside the cells, where it cannot bind receptors and send signals anymore. In our study, we show that cells from the mitral valve of patients with DMR with the ‘long-long’ genetic variant were more prone to react to serotonin in a way that could change the shape of the mitral valve by producing more collagen. Patients with this variant needed mitral valve surgery more often than those with other variants. Additionally, ‘long-long’ mitral valve cells were more sensitive to fluoxetine, a widely used SSRI, than cells from other variants.”

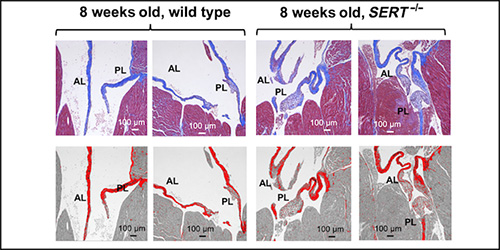

The researchers also studied in vivo mouse models using transgenic mice lacking the SERT gene and normal mice. They discovered that mice without a SERT gene developed thicker mitral valves and that normal mice treated with high doses of SSRIs also developed thickened mitral valves.

Top: Representative trichrome staining of heart sections of 8-week-old wild-type and SERT−/− mice showing the mitral valve anterior and posterior leaflets.

Bottom: The valve was stained with prico-sirius red to show collagen. SERT knockout mice had a thickened mitral valve compared to normal mice.

(Credit: Estibaliz Castillero, et al. Science Translational Medicine. 2023 Jan 4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.adc9606)

Study findings, which were published in the January 4, 2023, online issue of Science Translational Medicine, indicate that in DMR patients having the “long-long” variant and taking SSRIs lowers SERT activity in the mitral valve. “We suggest testing DMR patients for potential low SERT activity by genotyping them for 5-HTTLPR, which can be determined easily from a DNA sample obtained from the blood or a mouth swab,” notes Dr. Ferrari. “This may help identify patients who may need mitral valve surgery earlier. Promptly fixing a very leaky mitral valve would protect the heart and could prevent congestive heart failure.”

In this study, we showed that decreased SERT activity – either by 5-HTTLPR genotype or due to SSRI use – could induce a pathological phenotype in the mitral valve leaflets of patients with primary mitral regurgitation.

— Dr. Estibaliz Castillero, Dr. Giovanni Ferrari, and study co-authors

Implications for Treatment and Future Studies

“There are different compounding factors that may be decreasing the activity of SERT in the mitral valve: Taking an SSRI, the ‘long-long’ genotype, and degenerative mitral regurgitation itself,” adds Dr. Castillero. “When a patient with DMR has several of these factors, it may be a good idea to consider them at higher risk for the disease to worsen faster. Our study suggests that patients on SSRIs diagnosed with DMR could benefit from more regular follow-up to assess how the disease is progressing.”

Regarding the use of SSRIs to treat patients with psychiatric disorders, Dr. Castillero and Dr. Ferrari advise that if a patient has a family history of DMR, it may be worth a psychiatrist’s consideration when choosing a class of anti-depressant medication to prescribe. “Ongoing DMR may also influence clinical decisions on continuation of SSRI treatment, depending on how well the psychiatric symptoms are being managed by the treatment,” says Dr. Ferrari. “However, more clinical research needs to take place before patient guidelines can be considered evidence based. A conservative approach for now would be to counsel patients with DMR and depression to use an alternative to SSRI. Additional research may help determine if DMR patients who respond well to SSRIs should be regularly seen to assess progression of mitral degeneration, and whether DMR patients who are not responding well to SSRIs should consider switching to a non-SSRI antidepressant rather than raising the dose of the SSRI.”

Importantly, the researchers also found that healthy mitral valve cells tolerate SSRI treatment well, without acquiring a pathological phenotype. “Based on what we know, we don’t think that treatment with SSRI itself is enough to trigger degeneration of the mitral valve,” notes Dr. Ferrari. “Cardiac surgeons take into account all the medications that a patient is taking, but any modifications need to be carefully considered. Depression is known to have profound effects on health, including cardiovascular health, so the benefits of reducing depression symptoms may outweigh the risks of taking an SSRI.”