Retrograde cricopharyngeal dysfunction (RCPD) is characterized by four symptoms, including the inability to belch, abdominal bloating, gurgling noises from the chest, and excessive flatulence. RCPD was first described in 1987, but a reasonable treatment wasn't established until 2019. Most RCPD patients have been misdiagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome or gastroesophageal reflux disease, and they do not respond to the associated treatments.

Michael J. Pitman, MD, Chief of the Division of Laryngology and Director of The Center for Voice and Swallowing at NewYork-Presbyterian/

“My introduction to RCPD was through a patient. He showed me the 1987 paper, and asked me to cut his cricopharyngeus because he felt horrible and “couldn’t take it any longer”. I had an open mind and investigated his issue. I agreed to treat him and he had a great outcome. After I saw four or five patients with RCPD, they put my name on the patient driven NoBurp SubReddit, and the flood gates opened. It feels great to be able to help these patients who have an impaired quality of life and who are mistreated, misdiagnosed, or undiagnosed.”

It feels great to be able to help these patients who have an impaired quality of life and who are mistreated, misdiagnosed, or undiagnosed.

— Dr. Michael J. Pitman

The standard treatment for RCPD is direct laryngoscopy/

“The reason why the operating room has a much higher level of swallowing problems is that we're using a larger volume of Botox,” says Dr. Pitman. To reduce these swallowing issues post-procedure, and avoid the inconvenience and morbidity of the OR, he started performing in-office injections that do not require anesthesia.

“Apparently, I perform the highest volume of in-office injections in the country,” says Dr. Pitman. “It's about a 10-minute visit, with a one-minute injection, then they leave. Our goal is to get the in-office injection success rate as close as possible to the operating room result.”

Apparently, I perform the highest volume of in-office injections in the country. It's about a 10-minute visit, with a one-minute injection, then they leave. Our goal is to get the in-office injection success rate as close as possible to the operating room result.

— Dr. Michael J. Pitman

Studying the efficacy and safety of in-office and operating room BTX injections

Dr. Pitman and colleagues conducted a retrospective chart review to analyze the efficacy and safety of in-office versus operating room BTX injections for RCPD, and the results were published in Laryngoscope in 2024. The study's results demonstrate that in-office BTX injections for RCPD were safe; however, the success rates with in-office BTX injections were lower than those with operating room injections.

A patient receives an in-office botulinum toxin injection for no burp syndrome

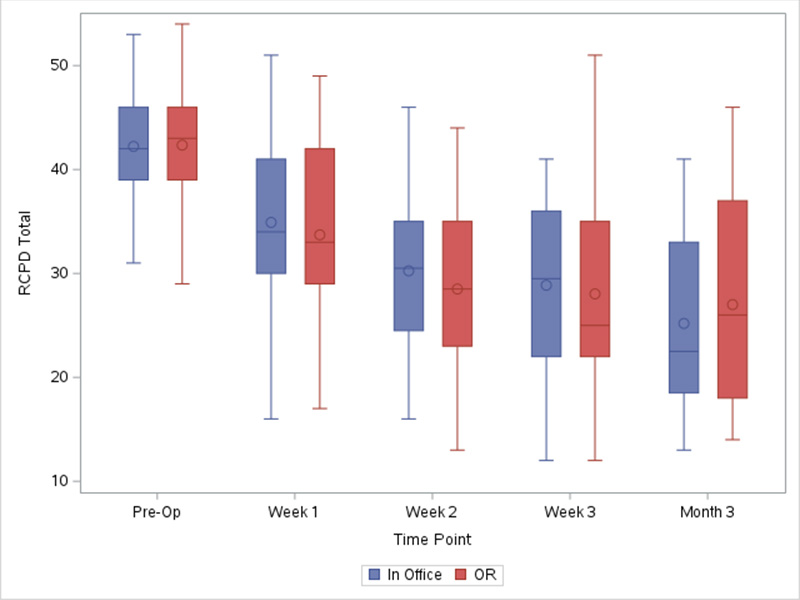

Dr. Pitman and colleagues also just completed a prospective study analyzing the efficacy and safety of operating room versus in-office BTX injections. The results from this study will be presented at the 104th Annual Meeting of the American Bronchoesophagological Association in May 2024. The study used a Likert scale to score RCPD symptoms as well as validated outcome measures, including the Eating Assessment Tool-10 (EAT-10) and the Generalized Anxiety Score-7 (GAD-7), to assess efficacy and safety.

“We found that all these patients have generalized anxiety, most likely due to their RCPD. After you treat them, their anxiety scores significantly decrease,” says Dr. Pitman.

Further, the results demonstrate that the outcomes of the operating room and in-office injections were similar. In-office injections require less Botox than in the operating room, so patients have fewer swallowing problems after the procedure. Therefore, it appears that the procedures are relatively equal in efficacy. However, in-office injections are associated with less morbidity than operating-room injections.

Graph of the RCPD total score decreasing over time with both in-office and operating room injections.

“Anecdotally, I still think that the operating room injections are a bit more successful than the office ones. In the office, we can only safely inject one side at a time compared to bilateral injections in the OR. I think that's why the operating room has a better result,” says Dr. Pitman. To overcome this issue, if after one office injection patients don’t have an ideal outcome, they return to the office for a second injection on the opposite side a few weeks later. This occurs 30% of the time. Dr Pitman believes this will “improve the equivalency between in-office and operating room injections. If both office injections fail, we take the patient to the operating room.”

As a next step, Dr. Pitman will analyze the response of patients who require a second office injection. He plans to compare these results to patients receiving one in-office or operating room injections.