Cytomegalovirus retinitis (CMV) is a rare and severe viral infection of the retina that primarily affects immunocompromised individuals such as those with HIV/AIDS or those who are immunosuppressed in the setting of bone marrow or organ transplantation. Though there have been significant improvements in outcomes with antiviral medications, CMV continues to be a sight-threatening condition that, if left untreated, can potentially lead to irreversible blindness.

Dr. Szilárd Kiss

“CMV is a ubiquitous infection, it's all around us,” says Szilárd Kiss, MD, an ophthalmologist and vitreoretinal specialist in the Department of Ophthalmology at NewYork-Presbyterian/

Current treatment focuses on both antiviral therapy and immune reconstitution, when possible. Antiviral therapies include systemic ganciclovir, valganciclovir, foscarnet, cidofovir, letermovir, off-label leflunomide; and intravitreal ganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir – alone or given in combination. While these agents are effective, each produces side effects and toxicities that some patients cannot tolerate. “There is about 10 to 15 percent of patients for whom either the side effect profile of those medications prevents them from taking the medication or the virus has mutated such that the traditional therapies don’t work,” says Dr. Kiss.

“Like many times in medicine, the impetus for our seeking a new treatment started with a patient with CMV retinitis who had exhausted all current treatment options,” continues Dr. Kiss, who reached out to his colleagues at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Researchers there had been effectively treating some types of blood cancers with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

“CAR T-cell therapy is one of the greatest advances in the 21st century and has shown remarkable efficacy with response rates in cancer patients who have failed traditional chemotherapy,” says Dr. Kiss. “We saw an opportunity to collaborate in finding a similar therapy and harnessing the immune system for treating CMV retinitis.”

In CAR T-cell therapy, cells are taken from a patient’s blood and manipulated in the lab by adding a gene for a receptor, which helps the T-cells attach to a specific cancer cell antigen. The CAR T-cells are then given back to the patient. To apply this novel treatment to CMV retinitis, T-cells are extracted from those individuals who had previous CMV infections. These CMV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytic (CTLs) donor cells are then banked and sorted based on their immune profile.

Dr. Szilárd Kiss has participated as a principal investigator in multiple prospective clinical trials and laboratory investigations.

“To make sure that the donor cells will not be rejected by the recipients, we conducted a major histocompatibility complex – MHC match – to the donor and the recipient,” says Dr. Kiss. “From the library of banked donor T-cells, we would locate the particular T-cell with the same cell surface MHC class markers as the patient. Those cytotoxic T-cells were then expanded and ultimately transfused into the patient to fight off the infection in the eye.”

Immunotherapy versus Standard of Care

Dr. Kiss recently led a multicenter retrospective cohort review of ocular outcomes in patients with active CMV retinitis who were evaluated at the Department of Ophthalmology at Weill Cornell Medicine from 2007 through 2019. The control group included patients who were treated with standard-of-care therapies (intravitreal or systemic antiviral therapies, or both, and, when relevant, immune reconstitution), and a study group treated with CMV-specific CTLs at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

The majority of the patients treated with the CMV-specific cytotoxic T-cells had stable or improved vision and rarely experienced complications associated with the CMV retinitis. This is the first proof-of-concept study showing that the eye can be treated with T-cell therapy similar to what is done in cancer patients.

— Dr. Szilárd Kiss

In the investigation, the results of which were published in the September 2021 issue of Ophthalmology Retina, 27 patients (36 eyes) met inclusion criteria: 7 patients (10 eyes) were treated with CMV-specific CTLs and 20 patients (26 eyes) were treated with standard-of-care therapies, with the following findings:

- 2 patients (28.6 percent, 4 eyes) received CMV-specific CTL therapy without concurrent systemic or intravitreal antiviral therapy

- 5 patients (71.4 percent, 6 eyes) continued to receive concurrent antiviral therapies

- Over an average follow-up of 33.4 months, resolution of CMV retinitis was achieved in 9 eyes (90 percent) treated with CMV-specific CTLs with best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) stabilizing (4 eyes) or improving (4 eyes) in 80 percent of eyes

“The majority of the patients treated with the CMV-specific cytotoxic T-cells had stable or improved vision and rarely experienced complications associated with the CMV retinitis,” says Dr. Kiss. “This is the first proof-of-concept study showing that the eye can be treated with T-cell therapy similar to what is done in cancer patients.”

Dr. Kiss and his colleagues concluded that CMV-specific CTL therapy may represent a novel monotherapy or adjunctive therapy, or both, for CMV retinitis, especially in eyes that are refractory to standard-of-care antiviral therapies. While T-cell therapy is still experimental, the study offers an indication as a potential treatment in clinical ophthalmology. “Intraocular tumors, either intraocular lymphoma or intraocular melanoma, may be amenable to T-cell therapy,” says Dr. Kiss. “In addition, transfusion of helper T-cells may also be used in uveitis, a group of disorders where the immune system attacks the eye itself. I could imagine that instead of using cytotoxic T-cells that go in there as the ‘troops,’ you use ‘diplomatic,’ helper T-cells to calm down an immune system that is attacking the eye.”

Case in Point

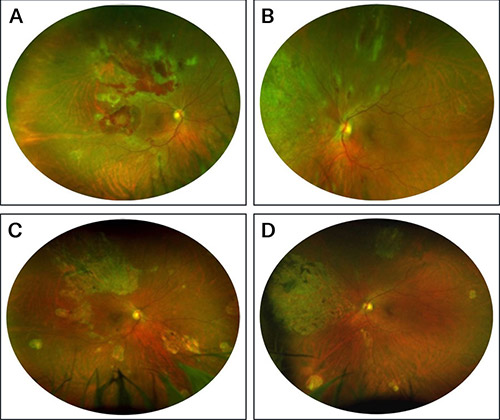

A patient with CMV retinitis treated with CMV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. (Courtesy of Dr. Szilárd Kiss)

In the images above: (A, B) Funduscopic examination revealed full-thickness retinal necrosis with hemorrhages consistent with CMV retinitis in both eyes. The patient underwent 2 rounds of CMV-specific CTL therapy, during which he received no other systemic or intravitreal antiviral therapies.

Dramatic consolidation and then resolution of the retinitis occurred within 3 months of initiating therapy. (C, D) Response was durable; funduscopic evaluation at 76 months after CMV-specific CTLs revealed chorioretinal scarring with no recurrence of retinitis, uveitis, macular edema, or retinal detachment.

“The CMV cytotoxic T-cell therapy is not yet FDA approved and only available in select centers,” adds Dr. Kiss. “The next step would be to conduct a larger prospective evaluation of the technology that could lead to FDA approval. It is extremely exciting because it represents a different approach to treating ocular disorders that’s never been done before.”